Thematic Dungeon Exploration (Firkraag's Maze)

After the tremendous success of my previous thread—I got 1(one) reply!!—I felt obligated to have another go. (Don't worry, I shall not spam the board with any more. But I have been meaning to dismantle this particular dungeon for a long time now - and I've limited myself to the big mysteries, too)

Let's get to it.

A Hidden Monastery, Desecrated

For our second exploration, I have picked Lord Firkraag’s dungeon. It’s a location that, even during my most mechanical runs through Baldur’s Gate II, I have never been able to ignore. Its architectural quirks and scattered remnants of a previous purpose are striking and peculiar, demanding interpretation even when the game offers little in the way of explicit answers.

Much of the dungeon’s history is lost, and the ruins are overrun with filth, orcs, and the remnants of Firkraag’s defilement. But among the ruin lie shadows—fragments of form and function that hint at something far more deliberate. And when assembled, these shadows tell a story of legacy, secrecy, and sacrilege.

Here is my thesis: this dungeon was once a hidden monastery, founded for the express purpose of guarding the tomb of King Strohm III, the Tethyrian monarch who gave his life to gravely wound and drive away a red dragon. That dragon was Firkraag, who is known to hold onto grudges long past the limits of his offenders’ lifespans. He has since found and systematically desecrated the site.

A Monastery in All but Name

Let’s deal with a common misconception: the game never explicitly calls the dungeon a monastery. There are only two in-game textual clues that link the site to religious function:

Still, I argue this was a monastery—because when we piece together the circumstantial evidence, the purpose and structure of the original complex come into focus.

Two Structures, Two Histories

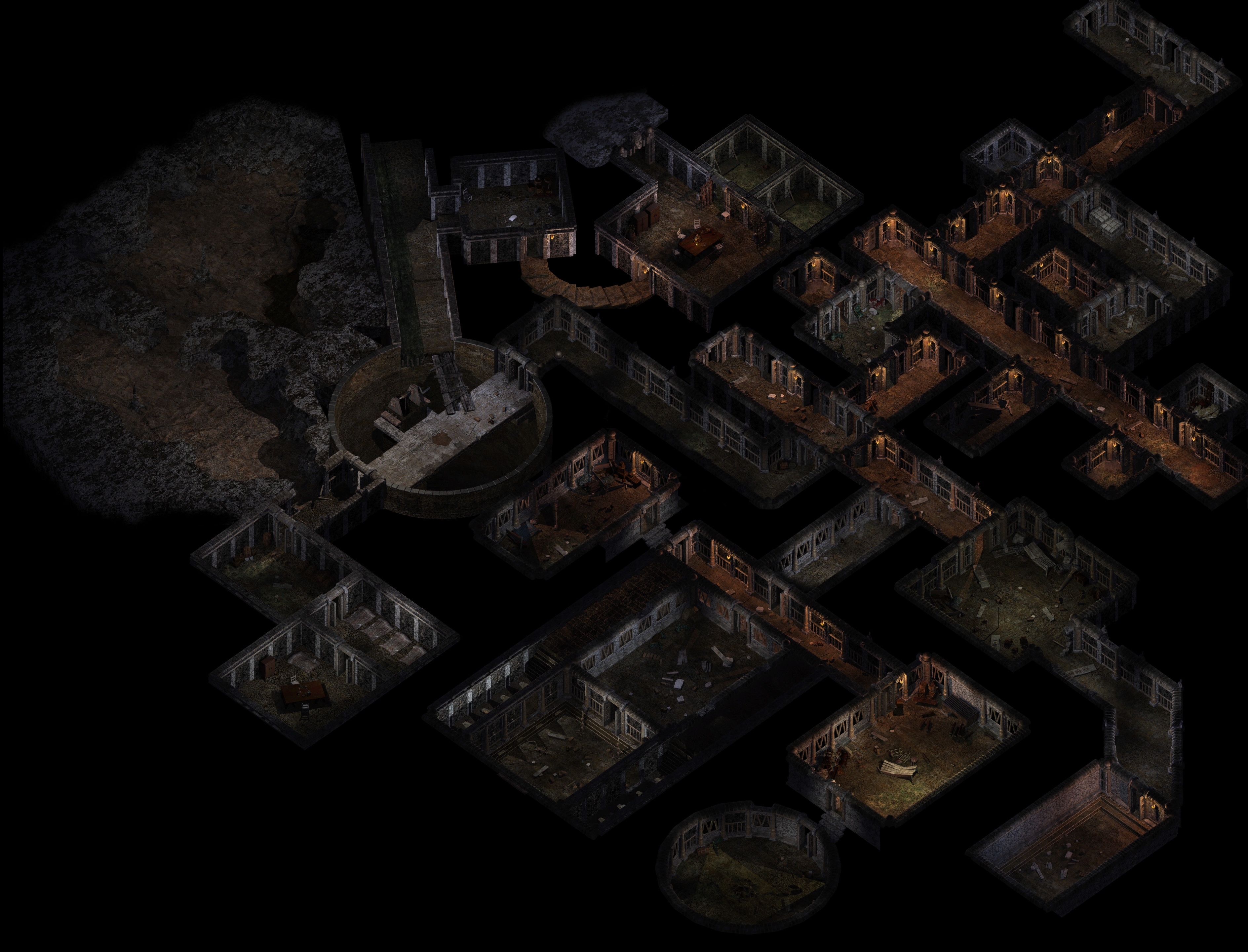

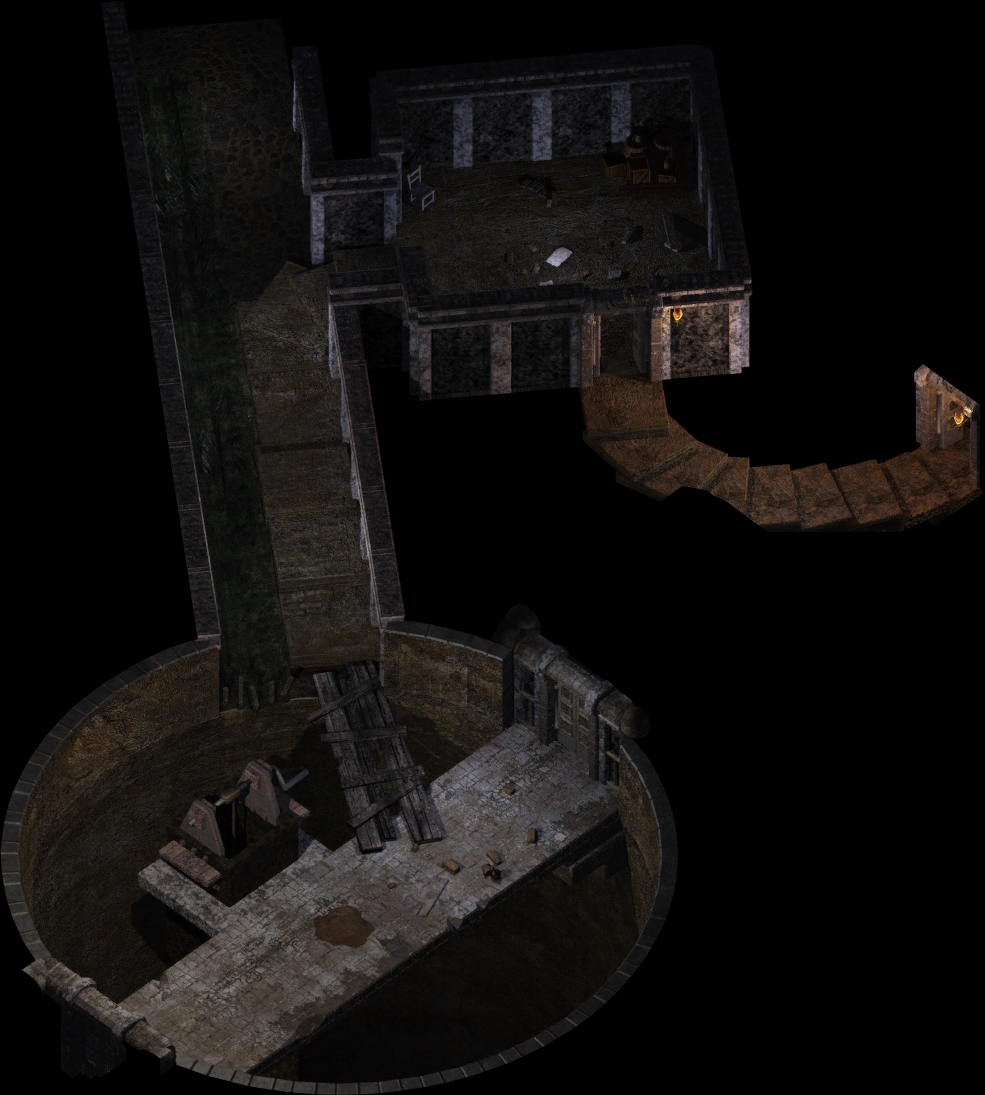

While the ruins are badly worn and much of the original detail is lost, there is a striking consistency to the architecture within the main complex—designated AR1202 in the game files. The patterns, materials, motifs etcetera are cohesive, all speaking to a single design philosophy and a unified construction effort. That consistency vanishes the moment you step outside AR1202. The natural cave preceding it (AR1201) and the heavily stylized “grand gate” at its mouth follow different aesthetics entirely.

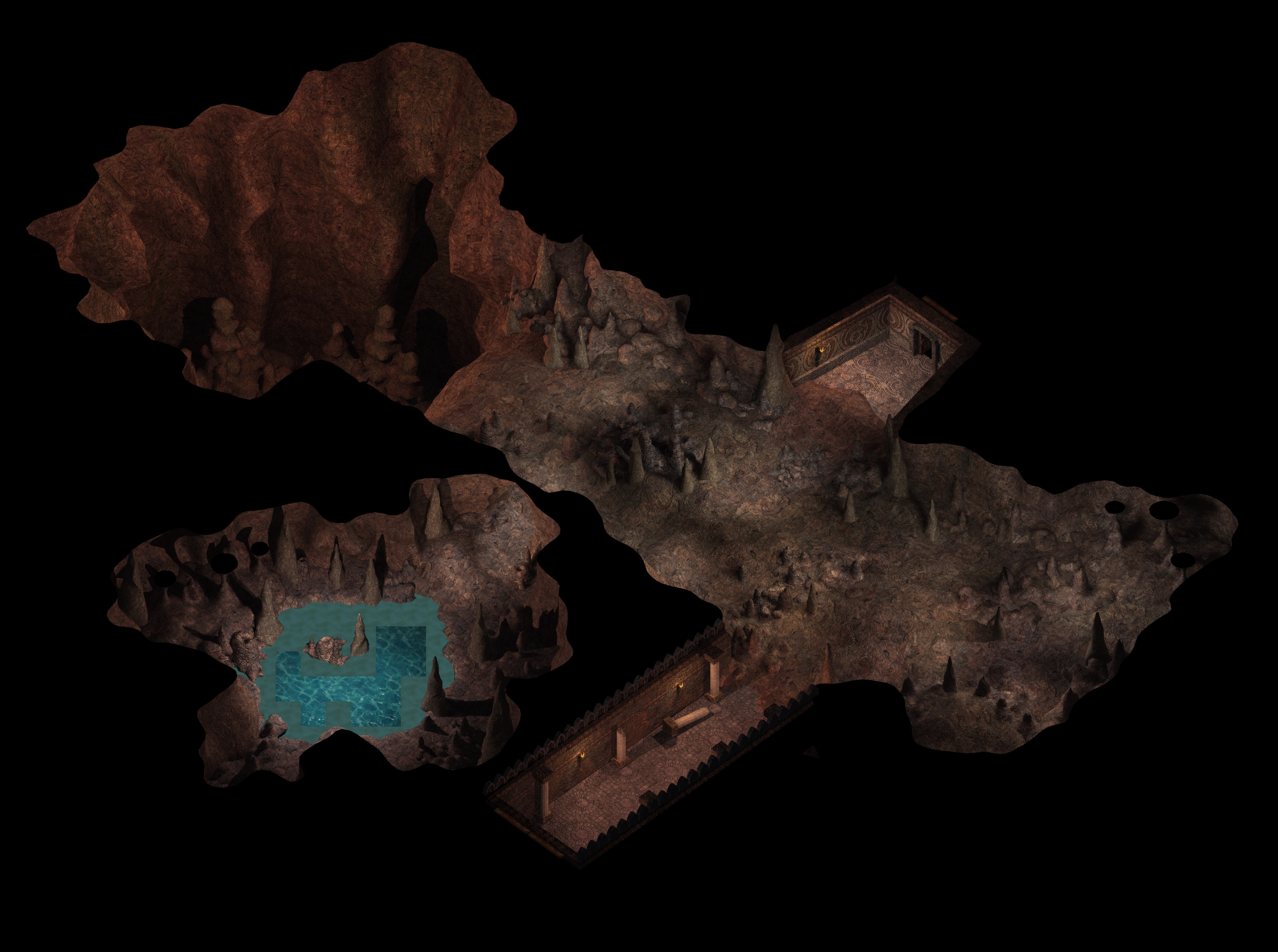

This strongly implies that the dungeon was originally self-contained. It was meant to be accessed only from within the cave—and even then, through a modest, unassuming entrance set into the rock wall. AR1202 was not designed to connect to the overwrought temple façade now sitting at the edge of the cliff. That structure, with its elaborate dragon motifs and theatrical scale, is wildly out of character with the rest of the complex. Its purpose seems less functional than declarative: a marker, a scar, a dragon’s signature.

The evidence for this later addition is not merely stylistic. The architecture does not align. The cave’s stalagmites are massive and undisturbed, meaning the rock formations have stood for many centuries. This wasn’t a cave that was excavated and then renaturalized—it was never fully developed. The path leading into the cave does not even point toward the path leading into the dungeon. There was no serious attempt to integrate the old structure with the new front. Instead, the new gateway at the cave mouth was imposed onto the existing geography long after the fact.

All signs suggest this was a hidden complex, possibly never meant to be found. Which makes the construction of such a grandiose entryway all the more suspect. I propose this: the new entrance was built not by the original founders, but by the ruin’s conqueror—Firkraag himself. And it wasn’t built for practical use. It was a statement.

A Life of Silence: The Inward Order

Let us, for now, accept that the original inhabitants chose to hide themselves away in darkness—for some purpose. One might still argue that this was a military outpost. But the ornamented walls tell a different story. This place was not built merely to house soldiers. Armies demand economy and expedience; they do not carve intricate flourishes into stone.

To bring people into such isolation—and keep them there—requires a powerful motive. If the seclusion served no martial function, then it must have been spiritual. The evidence points to a self-contained, inward-facing community, marked by austerity and ritual. Not a garrison, but an order.

The Ritual of the Pit: Water, Symbol, and Speculation

• The Mystery of the Pit

Unfortunately, there is little physical evidence left of the complex’s original purpose. The place has been thoroughly despoiled, and aside from bare walls and a few scattered keys, the past is nearly silent. Even the so-called chapel bears no distinguishing features—only the existence of a “Chapel Key” hints at its identity.

But there is one room that refuses to fade into the background. I’ve stumbled over its strangeness on every playthrough of this dungeon, though I only recently began analyzing it seriously. I now believe this space holds the key to understanding the entire structure.

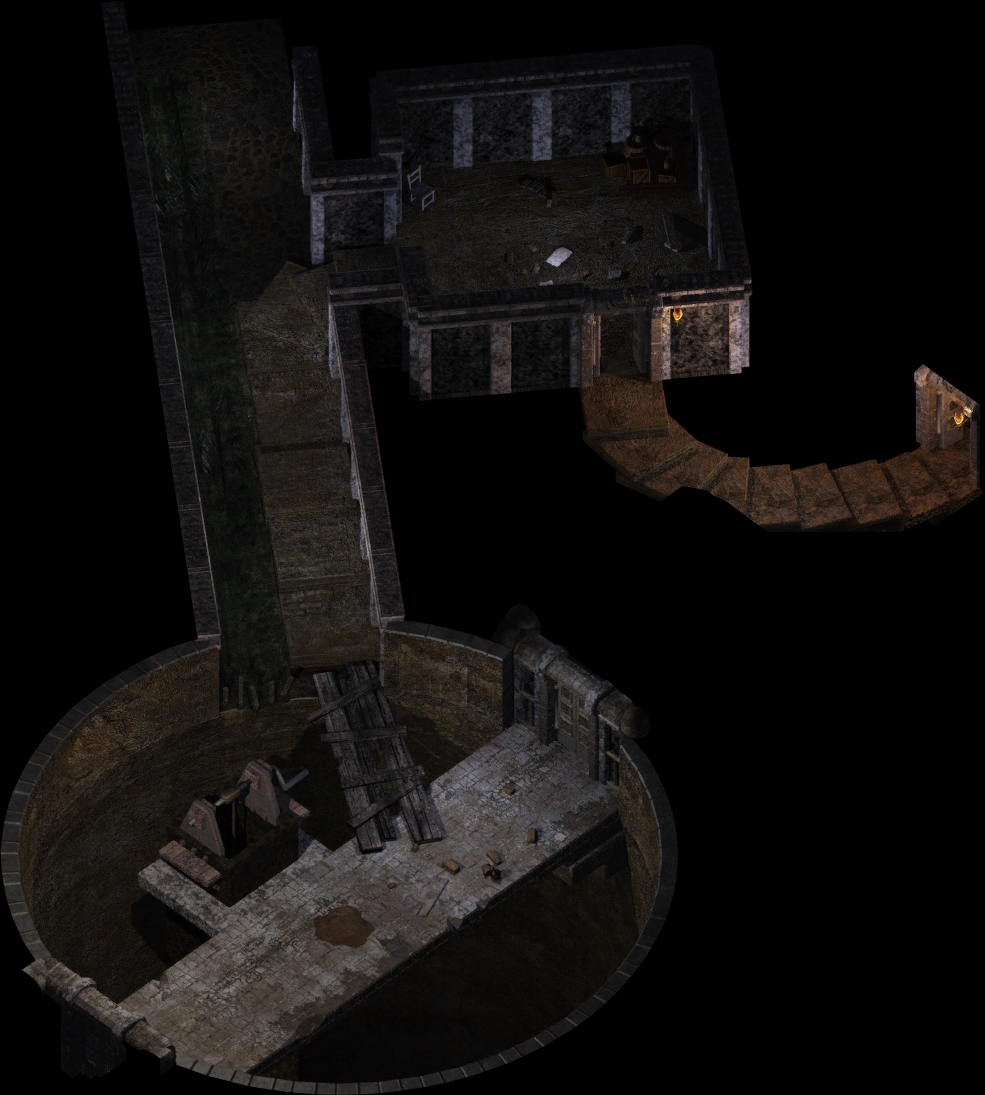

The orcs, faced with a deep, dark pit cutting across their path, built an improvised bridge. It’s easy to take that bridge at face value and move on. But let’s pause. There is a pit. And it matters.

The stone bridge shows no signs of ever having extended to the other side. The direct line forward from this tunnel is blocked by the well. And yet the upper parts follow the same cohesive architectural style as the rest of this dungeon. They were designed to be disconnected.

Before I make any claims, let me present the clues:

• A Pool of Purpose

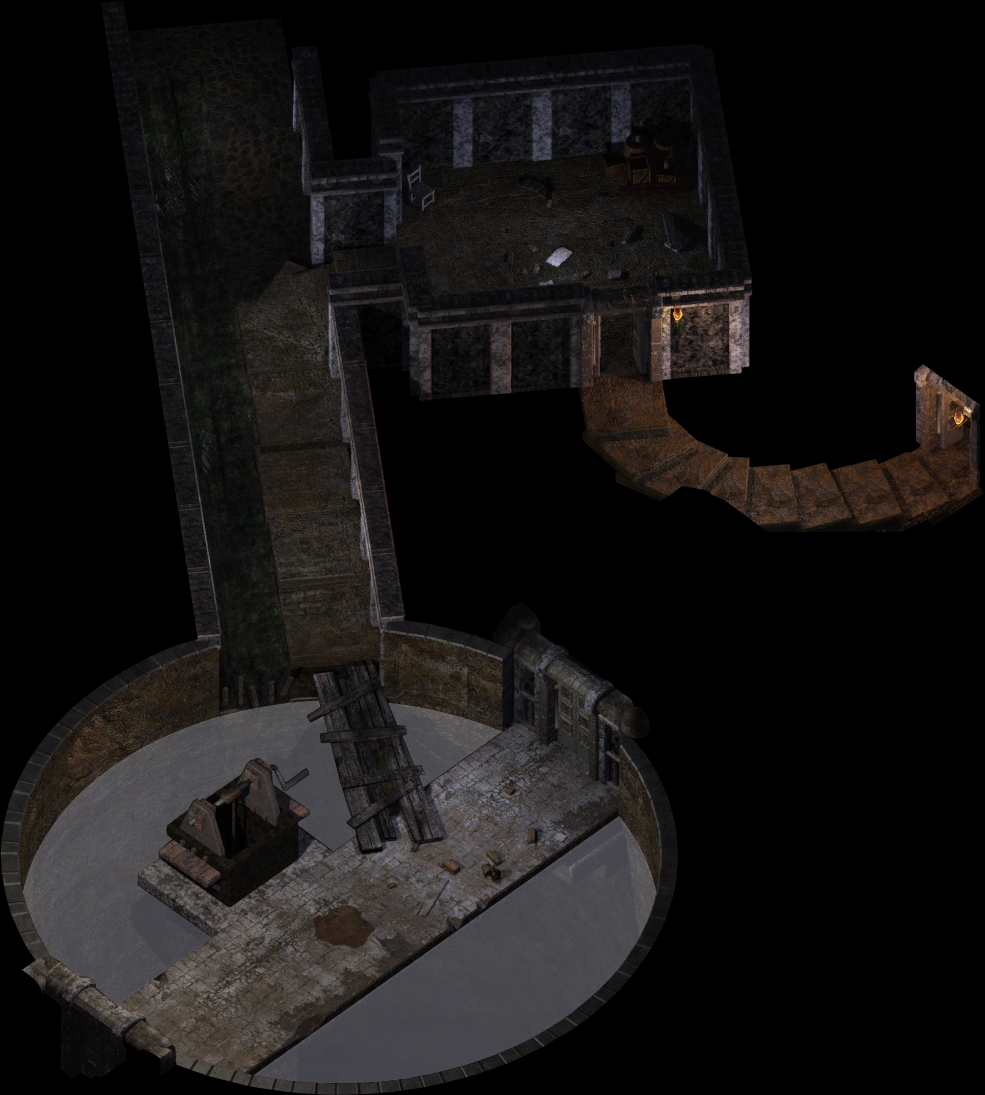

I propose that this pit was once filled with water. The shadows I’ve just mentioned align beautifully to mark out a consistent water level.

This basin, I believe, was originally fed by the upper tunnel.

But wait, you might ask—wouldn’t that risk flooding the rooms connected to that tunnel?

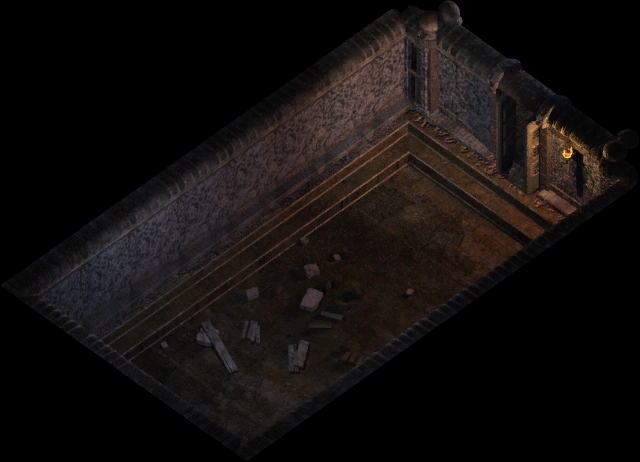

It’s difficult to see, but take another look at the stone slabs. (disturbingly brightened with my amazing editing skills)

They are stacked atop one another like the steps of a submerged staircase, rising gradually as they approach the adjacent room. The effect is easy to miss, since the wall details obscure things, but the implication is clear: the floor of that room sits at a higher elevation than the tunnel. It was protected from rising water.

Still, elevation alone wouldn’t suffice. There must once have been some mechanism to control the water’s flow. I’ll return to that question later.

So: the pit was once a pool. What insights does that give us?

Look now to the well. It stands on a platform that resembles the adjacent bridge, yet is clearly a separate construction. The bridge rests on two stone protrusions. The well’s platform, by contrast, sits atop a distinct substructure—inevitably hollow—built with a scale and solidity that makes little sense in the pit’s current, dry state.

But imagine the past: the well once rose from the middle of a deep body of water, its shaft descending through the surface into the depths below.

This design defies practicality.

It defies aesthetics, too. The bridge is geometrically centered, a straight line bisecting the circular chamber. But the well breaks that harmony. It’s awkwardly placed, clashing with the tunnel’s axis. It does not appear to have been part of the original plan. It was added with intent—but not convenience—in mind.

There’s an old joke in archaeology: whenever we find something we don’t understand, we declare it “ritualistic.”

Well then—a well in the middle of a pool of water.

And a tunnel, leading toward the heart of the complex, separated by a deep basin and filled with a shallow stream of running water.

Yes, I am calling the area beyond this point the heart of the structure. It was not exactly inaccessible—so it was unlikely to be a vault or treasury—but reaching it demanded effort. It was a process. A transition. Almost a rite.

• A Ritual of Resistance

This, then, is the ceremony I envision:

The monks would cast Water Walk and gather around the well, standing on the surface of the pool. One by one, they would approach the crank, drawing water from the very bottom of the shaft to fill their ceremonial cups. It was a deliberate act—a rejection of surface water in favor of the deeper, truer source. And it was an effortful task, a physical symbol of spiritual discipline: to draw sustenance not from ease, but from depth and intention.

Then they would proceed up the tunnel. Solemnly, they would walk against the current, pressing onward through the shallow stream. Again, it was a symbolic rejection—of passivity, of drift, of the mundane flow of the world. They moved quite literally against the stream, step by soaked step, to reach their inner sanctum and offer their daily prayers.

If we were to hazard a guess at the god they venerated, Istishia—elemental lord of water—might be a candidate. But we have no direct evidence. The ritual remains speculative. The divine name, uncertain.

What does remain, however, is this: a structure built with intention, with meaning embedded in its stones. A hidden place whose very architecture tells us that effort, reflection, and spiritual resilience once defined the rhythm of life here.

More Than Meets the Map

Earlier, I claimed that there must have been a mechanism to control the flow of water. Yet no trace of such a device exists in the accessible dungeon

Since I stand by the theory of the flooded chamber, I conclude that parts of the original complex are missing—sections the player is never allowed to enter.

There are other signs of this as well.

Consider the entry hall.

It is flanked by two cage rooms, forming a rather solid defensive position (if poorly staffed by orcs). But on both sides, stairs lead upward—to nowhere. There are no area transition points. From a tactical perspective, defenders should have had the option to retreat to higher ground or call for reinforcements. From a visual perspective, those staircases imply the presence of additional levels.

In my personal headcanon, I chalk it up to disinterest: my protagonist took a quick glance at the foul-smelling orc barracks above and turned around without a second thought.

Then there’s the matter of scale.

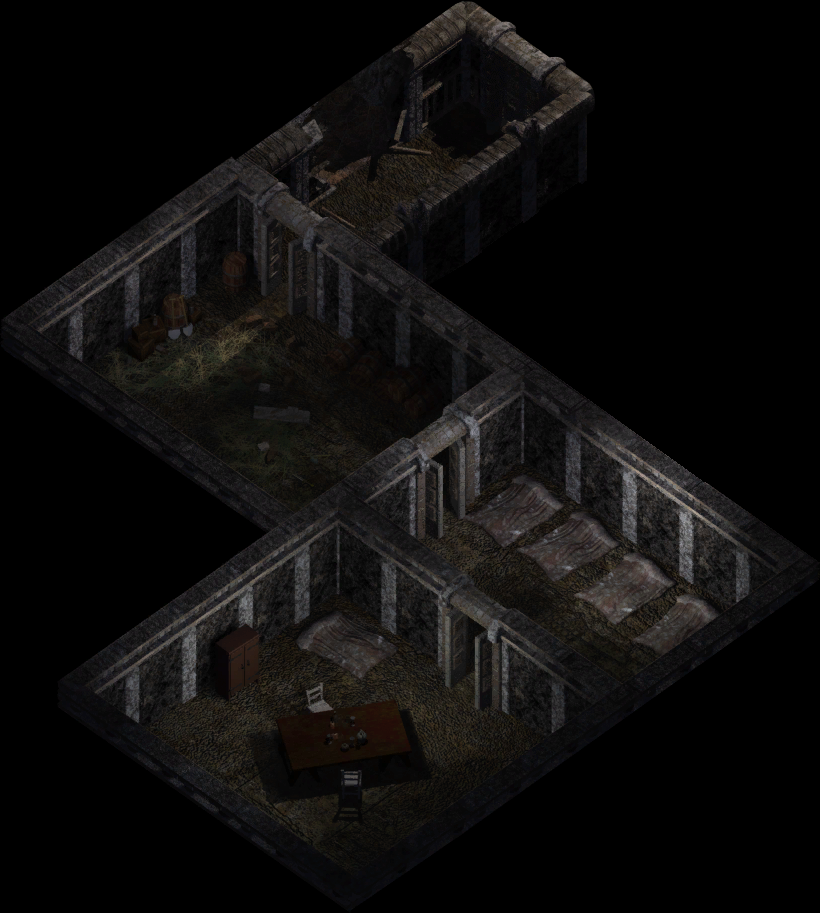

The dormitory we see is modest in size, especially when compared to the kitchen and what I assume to be the pantry. That kitchen was meant to serve more than a handful of ascetics.

There is another potential dormitory across the bridge, but its placement suggests it was restricted to higher-ranking monks. If that’s the case, it would not have contained many beds.

All this leads me to believe we are only seeing part of the original structure. Rooms are missing. Stairs lead nowhere. Crucial architectural logic—defensive, domestic and otherwise—is conspicuously incomplete.

Having surveyed the architecture—the visible and the conspicuously absent—we are left with a final set of questions. Who created this place? Why hide it so thoroughly, and with such elaborate precautions? The answer lies not in the stonework itself, but in the history that casts its shadow over it: the struggle and death of King Strohm III, and the lengths to which his heir went to keep his legacy safe.

A King's Burial and the Order That Watched Over It

• A Legacy Half-Forgotten

King Strohm’s legacy is both subdued and unavoidable. In gameplay terms, his tomb is treated as a minor sidequest—but you cannot reach the dungeon’s master without encountering Samia, who introduces you to the king's resting place.

Despite that unavoidable presence, the king’s background is barely touched upon. Samia, the self-styled academic, mentions he was from Tethyr, but wrongly attributes his death to treachery. The dialogue then veers quickly into quest logistics. Any questions the player might have—such as why a Tethyrian king lies buried in Amn—are quietly swept aside.

The efreeti guardians offer more. They don’t name the beast, but they paint a clear picture of a red dragon. And from them, we learn what Samia omits: Strohm III died not to betrayal, but in battle—buying victory with his life. He struck the dragon so grievously that it was forced to flee, thus saving many lives.

They also tell us that the dragon was allied with the drow Strohm III fought.

• A Funeral Across Borders

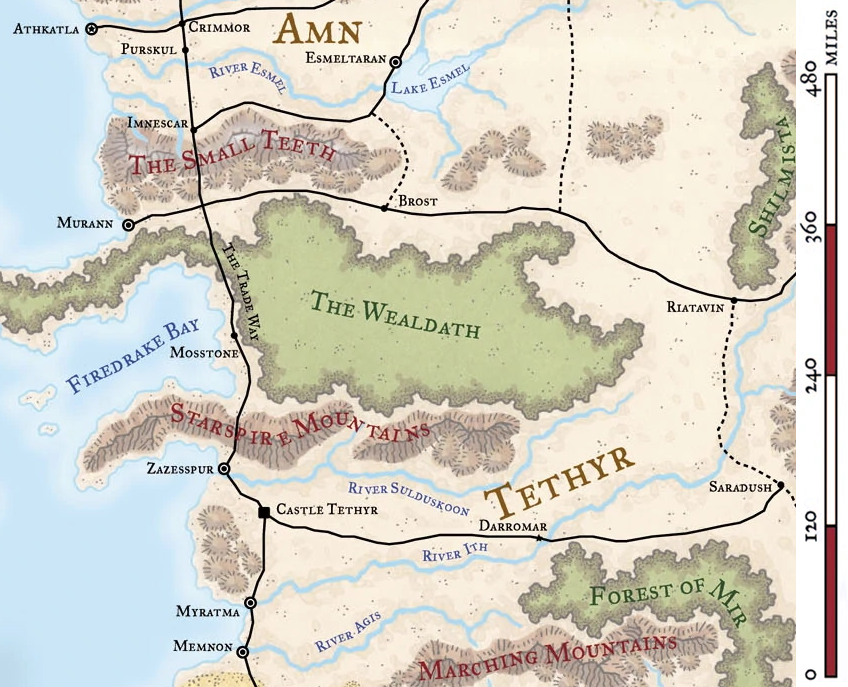

According to the Forgotten Realms wiki, Strohm III’s war against the drow began in 742 DR, eventually encompassing more than 30 battles, mostly around the Forest of Mir and the Marching Mountains. But he didn’t die until 769 DR—twenty-seven years later. Was that still the same war? Even if it was, we don’t know if he died in the same region.

Still, in the absence of contradicting evidence, I’ll assume he did—and that his body was deliberately transported across borders to be buried somewhere no one would ever think to look.

You might argue that I’m creating my own evidence—that there wouldn’t need to be a relocation if he died here in Amn. But in that case secrecy would have been impossible. A battlefield has many witnesses. If Strohm IV then started digging in the area, people would quickly put two and two together.

That would defeat the purpose. No matter how much he distrusted his countrymen, Strohm IV would’ve been safer bringing his father’s body back home.

The Book of King Strohm III makes this clear: Strohm IV went to great efforts to safeguard the tomb, fearing graverobbers. It follows that the tomb’s location was thoroughly hidden—even from allies. Especially from allies.

• Sworn to the Grave

Roughly 600 years ago, Strohm IV had this underground complex constructed. He must also have carefully chosen its guardians.

The efreeti he summoned to guard the tomb itself are timeless. That fits. But if all he needed was permanence, why not bolster them with other time-defiant defenders—liches, wraiths, or wards?

Yet the dungeon has a kitchen. With a chimney. That detail alone proves the complex was intended for mortal inhabitants. Orcs certainly didn’t install the chimney—and the makeshift plank bridge they laid over the pit shows they couldn’t manage serious construction. So Strohm IV meant for this place to be inhabited by humans. Or something very like them.

But their life would have been harsh.

To protect the tomb’s secret, Strohm IV would have denied them all ties that might lead to discovery: no messages, no visitors, no family. No one could know the tomb existed. That left them only one realm in which to live: the spiritual.

They weren’t soldiers. They were something else: a hidden monastic order. Self-sustaining. Enduring. Silent. Devout.

Monks.

Firkraag’s Desecration

Nothing lasts forever—not even the best-kept secret.

This dungeon was created to honor a man who once gravely wounded a red dragon. One day, that dragon returned.

The cave’s current entrance, with its grand gate and overblown architecture, gives the impression of a ruined temple. But Firkraag did not design this entrance to elevate the site. He did it to deface it. His contempt for the complex is clearest not in its physical state, but in his refusal to set foot inside it. Past the grand gate, the dragon always turns left, avoiding the dungeon entirely. He has carved out his own tunnel—painstakingly dug—to lead directly to his private retreat. Rather than repurposing the monastery, he defaced it with a monument to himself. The message is unsubtle: Firkraag was here. Strohm III was nothing.

Even this grand new entrance is crumbling, though not yet desecrated. Firkraag appears to maintain it just enough to preserve the impression of his own grandeur. He won’t tolerate his orcs sullying it with filth. From the cave’s entry to the dungeon door, there is decay but no garbage. I suspect that at some point, Firkraag had this passage rebuilt when it became too ruinous for his pride to bear. But the rest of the dungeon? He is likely content to see it collapse. In the meantime, he has allowed his orcs to ransack and profane it completely. They have violated it as thoroughly as he hoped they would.

As for the hall that Firkraag now occupies—decorated with draconic grimaces and carved mockeries—it may once have been the original inner sanctum of the monastery. In creating his new tunnel from the natural cave, he appears to have pierced a water vein, flooding the back of his chamber and forming a lake. I suspect this is what caused the drying of the ceremonial pool I discussed earlier.

Let's get to it.

A Hidden Monastery, Desecrated

For our second exploration, I have picked Lord Firkraag’s dungeon. It’s a location that, even during my most mechanical runs through Baldur’s Gate II, I have never been able to ignore. Its architectural quirks and scattered remnants of a previous purpose are striking and peculiar, demanding interpretation even when the game offers little in the way of explicit answers.

Much of the dungeon’s history is lost, and the ruins are overrun with filth, orcs, and the remnants of Firkraag’s defilement. But among the ruin lie shadows—fragments of form and function that hint at something far more deliberate. And when assembled, these shadows tell a story of legacy, secrecy, and sacrilege.

Here is my thesis: this dungeon was once a hidden monastery, founded for the express purpose of guarding the tomb of King Strohm III, the Tethyrian monarch who gave his life to gravely wound and drive away a red dragon. That dragon was Firkraag, who is known to hold onto grudges long past the limits of his offenders’ lifespans. He has since found and systematically desecrated the site.

A Monastery in All but Name

Let’s deal with a common misconception: the game never explicitly calls the dungeon a monastery. There are only two in-game textual clues that link the site to religious function:

- If you approach the dungeon gate before defeating the knights, you’re told: “The entrance to the ruined temple appears blocked.”

- There’s a “Chapel Key,” described as having been found in “the ruined chapel of the complex in the Windspear Hills.”

Still, I argue this was a monastery—because when we piece together the circumstantial evidence, the purpose and structure of the original complex come into focus.

Two Structures, Two Histories

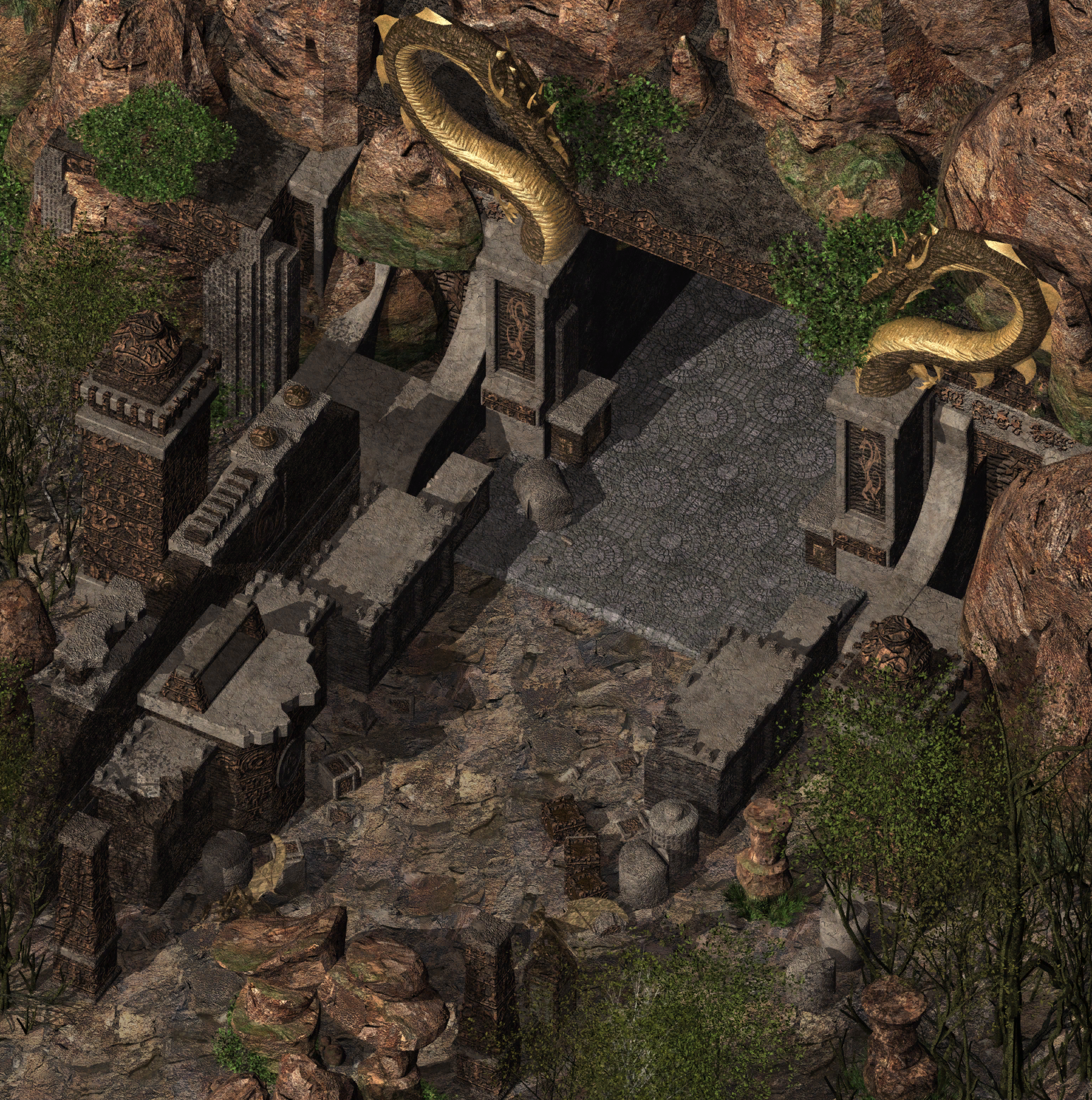

While the ruins are badly worn and much of the original detail is lost, there is a striking consistency to the architecture within the main complex—designated AR1202 in the game files. The patterns, materials, motifs etcetera are cohesive, all speaking to a single design philosophy and a unified construction effort. That consistency vanishes the moment you step outside AR1202. The natural cave preceding it (AR1201) and the heavily stylized “grand gate” at its mouth follow different aesthetics entirely.

This strongly implies that the dungeon was originally self-contained. It was meant to be accessed only from within the cave—and even then, through a modest, unassuming entrance set into the rock wall. AR1202 was not designed to connect to the overwrought temple façade now sitting at the edge of the cliff. That structure, with its elaborate dragon motifs and theatrical scale, is wildly out of character with the rest of the complex. Its purpose seems less functional than declarative: a marker, a scar, a dragon’s signature.

The evidence for this later addition is not merely stylistic. The architecture does not align. The cave’s stalagmites are massive and undisturbed, meaning the rock formations have stood for many centuries. This wasn’t a cave that was excavated and then renaturalized—it was never fully developed. The path leading into the cave does not even point toward the path leading into the dungeon. There was no serious attempt to integrate the old structure with the new front. Instead, the new gateway at the cave mouth was imposed onto the existing geography long after the fact.

All signs suggest this was a hidden complex, possibly never meant to be found. Which makes the construction of such a grandiose entryway all the more suspect. I propose this: the new entrance was built not by the original founders, but by the ruin’s conqueror—Firkraag himself. And it wasn’t built for practical use. It was a statement.

A Life of Silence: The Inward Order

Let us, for now, accept that the original inhabitants chose to hide themselves away in darkness—for some purpose. One might still argue that this was a military outpost. But the ornamented walls tell a different story. This place was not built merely to house soldiers. Armies demand economy and expedience; they do not carve intricate flourishes into stone.

To bring people into such isolation—and keep them there—requires a powerful motive. If the seclusion served no martial function, then it must have been spiritual. The evidence points to a self-contained, inward-facing community, marked by austerity and ritual. Not a garrison, but an order.

The Ritual of the Pit: Water, Symbol, and Speculation

• The Mystery of the Pit

Unfortunately, there is little physical evidence left of the complex’s original purpose. The place has been thoroughly despoiled, and aside from bare walls and a few scattered keys, the past is nearly silent. Even the so-called chapel bears no distinguishing features—only the existence of a “Chapel Key” hints at its identity.

But there is one room that refuses to fade into the background. I’ve stumbled over its strangeness on every playthrough of this dungeon, though I only recently began analyzing it seriously. I now believe this space holds the key to understanding the entire structure.

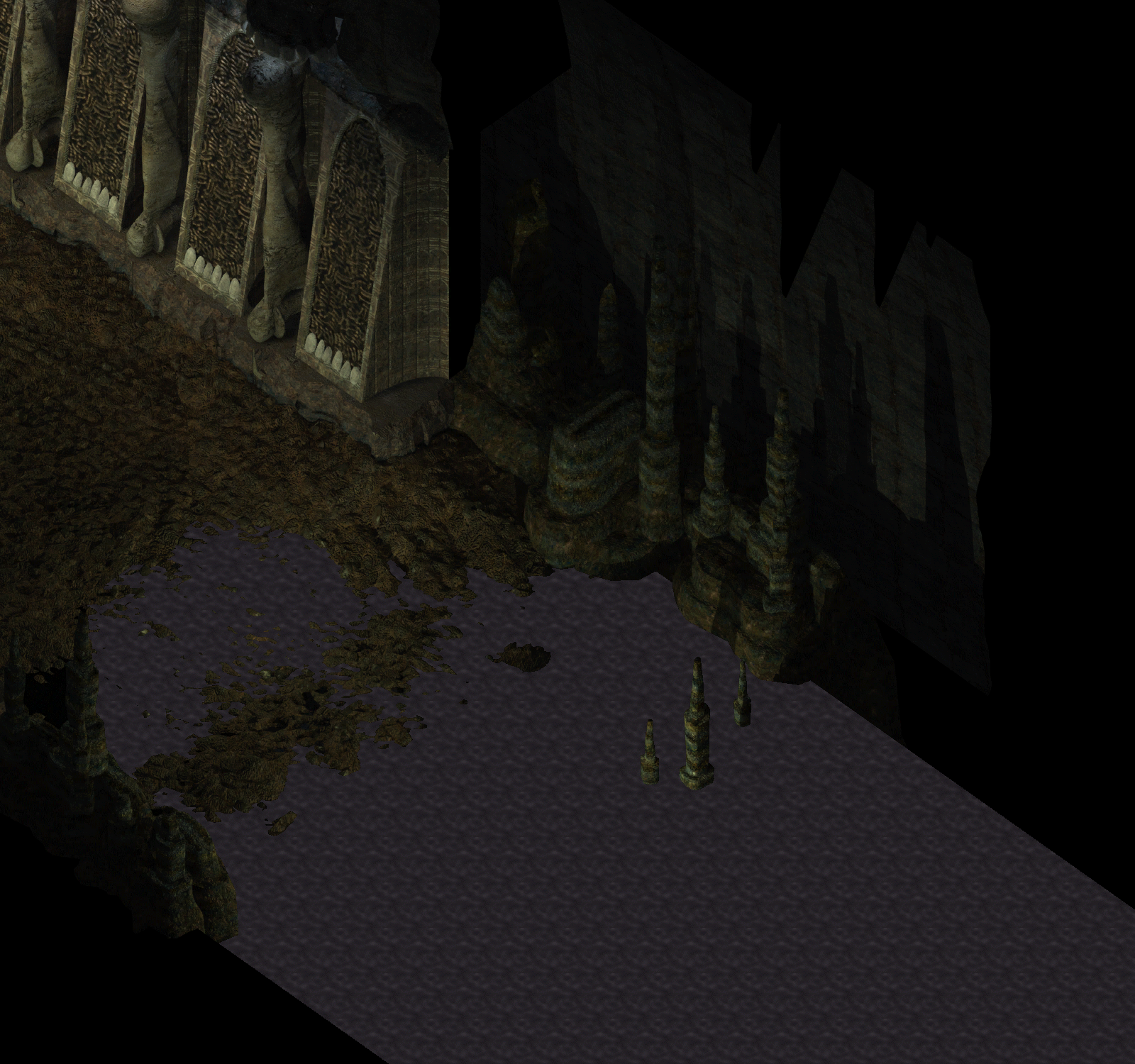

The orcs, faced with a deep, dark pit cutting across their path, built an improvised bridge. It’s easy to take that bridge at face value and move on. But let’s pause. There is a pit. And it matters.

The stone bridge shows no signs of ever having extended to the other side. The direct line forward from this tunnel is blocked by the well. And yet the upper parts follow the same cohesive architectural style as the rest of this dungeon. They were designed to be disconnected.

Before I make any claims, let me present the clues:

- The well yields only muddy water now, implying it once drew from a more robust source.

- The disconnected tunnel is visibly wet on the left side, while the right side is elevated with laid stone slabs.

- The walls of the pit are discolored below the level of the bridge, as if stained by long-standing water.

• A Pool of Purpose

I propose that this pit was once filled with water. The shadows I’ve just mentioned align beautifully to mark out a consistent water level.

This basin, I believe, was originally fed by the upper tunnel.

But wait, you might ask—wouldn’t that risk flooding the rooms connected to that tunnel?

It’s difficult to see, but take another look at the stone slabs. (disturbingly brightened with my amazing editing skills)

They are stacked atop one another like the steps of a submerged staircase, rising gradually as they approach the adjacent room. The effect is easy to miss, since the wall details obscure things, but the implication is clear: the floor of that room sits at a higher elevation than the tunnel. It was protected from rising water.

Still, elevation alone wouldn’t suffice. There must once have been some mechanism to control the water’s flow. I’ll return to that question later.

So: the pit was once a pool. What insights does that give us?

Look now to the well. It stands on a platform that resembles the adjacent bridge, yet is clearly a separate construction. The bridge rests on two stone protrusions. The well’s platform, by contrast, sits atop a distinct substructure—inevitably hollow—built with a scale and solidity that makes little sense in the pit’s current, dry state.

But imagine the past: the well once rose from the middle of a deep body of water, its shaft descending through the surface into the depths below.

This design defies practicality.

It defies aesthetics, too. The bridge is geometrically centered, a straight line bisecting the circular chamber. But the well breaks that harmony. It’s awkwardly placed, clashing with the tunnel’s axis. It does not appear to have been part of the original plan. It was added with intent—but not convenience—in mind.

There’s an old joke in archaeology: whenever we find something we don’t understand, we declare it “ritualistic.”

Well then—a well in the middle of a pool of water.

And a tunnel, leading toward the heart of the complex, separated by a deep basin and filled with a shallow stream of running water.

Yes, I am calling the area beyond this point the heart of the structure. It was not exactly inaccessible—so it was unlikely to be a vault or treasury—but reaching it demanded effort. It was a process. A transition. Almost a rite.

• A Ritual of Resistance

This, then, is the ceremony I envision:

The monks would cast Water Walk and gather around the well, standing on the surface of the pool. One by one, they would approach the crank, drawing water from the very bottom of the shaft to fill their ceremonial cups. It was a deliberate act—a rejection of surface water in favor of the deeper, truer source. And it was an effortful task, a physical symbol of spiritual discipline: to draw sustenance not from ease, but from depth and intention.

Then they would proceed up the tunnel. Solemnly, they would walk against the current, pressing onward through the shallow stream. Again, it was a symbolic rejection—of passivity, of drift, of the mundane flow of the world. They moved quite literally against the stream, step by soaked step, to reach their inner sanctum and offer their daily prayers.

If we were to hazard a guess at the god they venerated, Istishia—elemental lord of water—might be a candidate. But we have no direct evidence. The ritual remains speculative. The divine name, uncertain.

What does remain, however, is this: a structure built with intention, with meaning embedded in its stones. A hidden place whose very architecture tells us that effort, reflection, and spiritual resilience once defined the rhythm of life here.

More Than Meets the Map

Earlier, I claimed that there must have been a mechanism to control the flow of water. Yet no trace of such a device exists in the accessible dungeon

Since I stand by the theory of the flooded chamber, I conclude that parts of the original complex are missing—sections the player is never allowed to enter.

There are other signs of this as well.

Consider the entry hall.

It is flanked by two cage rooms, forming a rather solid defensive position (if poorly staffed by orcs). But on both sides, stairs lead upward—to nowhere. There are no area transition points. From a tactical perspective, defenders should have had the option to retreat to higher ground or call for reinforcements. From a visual perspective, those staircases imply the presence of additional levels.

In my personal headcanon, I chalk it up to disinterest: my protagonist took a quick glance at the foul-smelling orc barracks above and turned around without a second thought.

Then there’s the matter of scale.

The dormitory we see is modest in size, especially when compared to the kitchen and what I assume to be the pantry. That kitchen was meant to serve more than a handful of ascetics.

There is another potential dormitory across the bridge, but its placement suggests it was restricted to higher-ranking monks. If that’s the case, it would not have contained many beds.

All this leads me to believe we are only seeing part of the original structure. Rooms are missing. Stairs lead nowhere. Crucial architectural logic—defensive, domestic and otherwise—is conspicuously incomplete.

Having surveyed the architecture—the visible and the conspicuously absent—we are left with a final set of questions. Who created this place? Why hide it so thoroughly, and with such elaborate precautions? The answer lies not in the stonework itself, but in the history that casts its shadow over it: the struggle and death of King Strohm III, and the lengths to which his heir went to keep his legacy safe.

A King's Burial and the Order That Watched Over It

• A Legacy Half-Forgotten

King Strohm’s legacy is both subdued and unavoidable. In gameplay terms, his tomb is treated as a minor sidequest—but you cannot reach the dungeon’s master without encountering Samia, who introduces you to the king's resting place.

Despite that unavoidable presence, the king’s background is barely touched upon. Samia, the self-styled academic, mentions he was from Tethyr, but wrongly attributes his death to treachery. The dialogue then veers quickly into quest logistics. Any questions the player might have—such as why a Tethyrian king lies buried in Amn—are quietly swept aside.

The efreeti guardians offer more. They don’t name the beast, but they paint a clear picture of a red dragon. And from them, we learn what Samia omits: Strohm III died not to betrayal, but in battle—buying victory with his life. He struck the dragon so grievously that it was forced to flee, thus saving many lives.

They also tell us that the dragon was allied with the drow Strohm III fought.

• A Funeral Across Borders

According to the Forgotten Realms wiki, Strohm III’s war against the drow began in 742 DR, eventually encompassing more than 30 battles, mostly around the Forest of Mir and the Marching Mountains. But he didn’t die until 769 DR—twenty-seven years later. Was that still the same war? Even if it was, we don’t know if he died in the same region.

Still, in the absence of contradicting evidence, I’ll assume he did—and that his body was deliberately transported across borders to be buried somewhere no one would ever think to look.

You might argue that I’m creating my own evidence—that there wouldn’t need to be a relocation if he died here in Amn. But in that case secrecy would have been impossible. A battlefield has many witnesses. If Strohm IV then started digging in the area, people would quickly put two and two together.

That would defeat the purpose. No matter how much he distrusted his countrymen, Strohm IV would’ve been safer bringing his father’s body back home.

The Book of King Strohm III makes this clear: Strohm IV went to great efforts to safeguard the tomb, fearing graverobbers. It follows that the tomb’s location was thoroughly hidden—even from allies. Especially from allies.

• Sworn to the Grave

Roughly 600 years ago, Strohm IV had this underground complex constructed. He must also have carefully chosen its guardians.

The efreeti he summoned to guard the tomb itself are timeless. That fits. But if all he needed was permanence, why not bolster them with other time-defiant defenders—liches, wraiths, or wards?

Yet the dungeon has a kitchen. With a chimney. That detail alone proves the complex was intended for mortal inhabitants. Orcs certainly didn’t install the chimney—and the makeshift plank bridge they laid over the pit shows they couldn’t manage serious construction. So Strohm IV meant for this place to be inhabited by humans. Or something very like them.

But their life would have been harsh.

To protect the tomb’s secret, Strohm IV would have denied them all ties that might lead to discovery: no messages, no visitors, no family. No one could know the tomb existed. That left them only one realm in which to live: the spiritual.

They weren’t soldiers. They were something else: a hidden monastic order. Self-sustaining. Enduring. Silent. Devout.

Monks.

Firkraag’s Desecration

Nothing lasts forever—not even the best-kept secret.

This dungeon was created to honor a man who once gravely wounded a red dragon. One day, that dragon returned.

The cave’s current entrance, with its grand gate and overblown architecture, gives the impression of a ruined temple. But Firkraag did not design this entrance to elevate the site. He did it to deface it. His contempt for the complex is clearest not in its physical state, but in his refusal to set foot inside it. Past the grand gate, the dragon always turns left, avoiding the dungeon entirely. He has carved out his own tunnel—painstakingly dug—to lead directly to his private retreat. Rather than repurposing the monastery, he defaced it with a monument to himself. The message is unsubtle: Firkraag was here. Strohm III was nothing.

Even this grand new entrance is crumbling, though not yet desecrated. Firkraag appears to maintain it just enough to preserve the impression of his own grandeur. He won’t tolerate his orcs sullying it with filth. From the cave’s entry to the dungeon door, there is decay but no garbage. I suspect that at some point, Firkraag had this passage rebuilt when it became too ruinous for his pride to bear. But the rest of the dungeon? He is likely content to see it collapse. In the meantime, he has allowed his orcs to ransack and profane it completely. They have violated it as thoroughly as he hoped they would.

As for the hall that Firkraag now occupies—decorated with draconic grimaces and carved mockeries—it may once have been the original inner sanctum of the monastery. In creating his new tunnel from the natural cave, he appears to have pierced a water vein, flooding the back of his chamber and forming a lake. I suspect this is what caused the drying of the ceremonial pool I discussed earlier.

0

Comments

Don’t worry too much spamming this, it makes for a fun read.

This sounds like the premices of a mod I might add